The Stars Are Bright: An exhibition that captures the zeitgeist of its period.

- Nyadzombe Nyampenza

- Aug 26, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2022

by Nyadzombe Nyampenza

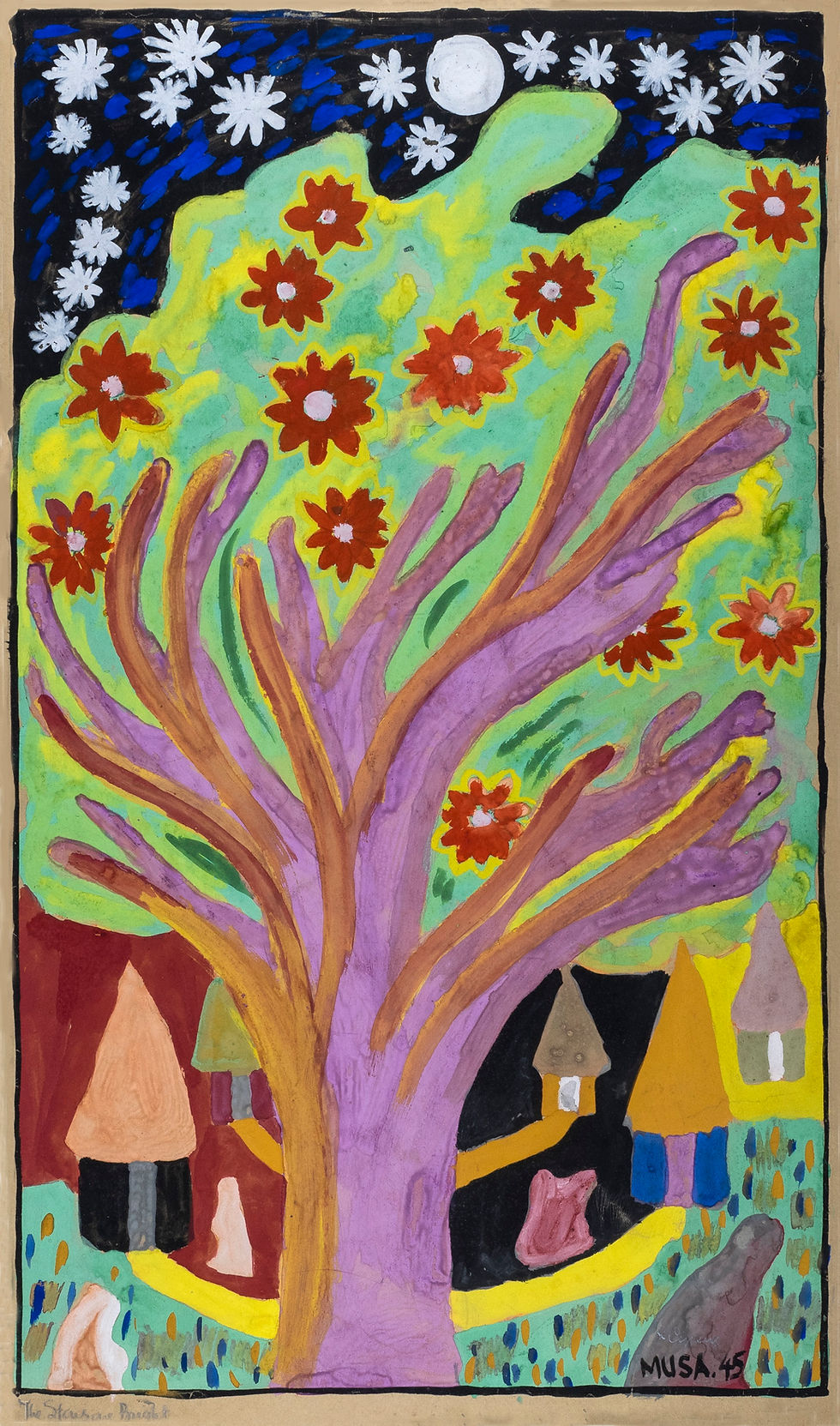

Barnabus Chiponza, How Beautiful Is Night (1945). Photo Debbie Sears © The Curtain Foundation. From the exhibition The Stars Are Bright

The Stars Are Bright is a comeback exhibition of paintings made by Cyrene Anglican Mission School art students between 1940 and 1947. In Zimbabwe, the exhibition is a homecoming show for the collection after a seventy-year odyssey abroad. The body of work by early indigenous students from the first school in the country to introduce art as a compulsory subject is an important historical legacy. The return of the collection invokes similar sentiments to the repatriation of Mukwatis’ walking staff, and other objects from Africa made during and before the colonial period.

Before showing at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Harare, the exhibition was at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo in April 2022, and before that at The Arches At Aberfoyle, in Honde Valley in November 2021. All three occasions mark the first time the collection has been presented to a local audience. Outside the country the collection was last shown in 2020 at the Theatre Courtyard Green Rooms in London, after the artworks laid in neglect for decades until they were rediscovered in 1978. The collection, which is currently in the care of The Curtain Foundation, is being presented by the Honde Valley Hydro Electric Power Trust.

Beginning from the well-received show at the Royal Watercolour Society in London in 1949, some artworks found new homes in private and public collections. One was purchased by Queen Elizabeth, and another was gifted to Queen Mother Elizabeth by Canon Edward ‘Ned’ Paterson. The artworks in the current exhibition have been selected from over 600 remaining from the initial tour, after being rescued from the basement of a disused church building in occupied by squatters in Shoreditch and sold on auction at Sothebys. In an ironic twist of fate, unsold work that may have been deemed materially inferior to the rest, has been thrust back into the spotlight. It is an impressive rebound that can be likened to the birth of ‘Impressionism’ at the Salon des Refusés in Paris, 1863.

The title of the exhibition is borrowed from an artwork by one of the artists, Musa Nyahwa. Whilst it conveys hope through the image of bright stars, it also implicitly acknowledges the darkness surrounding them. It is an apt metaphor for the undimmed hopes and aspirations of indigenous people during the colonial era. On the surface the paintings look pleasant with their vibrant colors and engaging subject matter. Upon reflection, the viewer is drawn way back into the past, and becomes engulfed by the darker aspects of the time.

Billing for the exhibition entices the viewer with a subtitle inviting them to see ‘’Zimbabwe through the eyes of its young painters from Cyrene (1940-1947).’’ The audience is expected to tap into the emotions, perception, and sensibilities of the artists who were aged between 9-19 years old. It is an exciting proposition for a socio-political study, for those wishing to understand what Zimbabwe was like 70 years ago.

Cyrene Mission School was opened in 1940 by Anglican clergyman, the Reverend Canon Edward ‘’Ned’’ Paterson, as a skills oriented school for African boys. Under the stewardship of the Anglican Church the Cyrene artists created their work in an environment that cultivated piety and a belief in human equality. At that time the country was called Rhodesia, a self-governing British colony established (in 1923) under White settlers most of whom believed in racial domination. Jonathan Ziberg notes that ‘’Cyrene became the most important national context for the promotion of liberal agendas and racial tolerance in a racially divided colonial society.’’

Curatorial statements describe the period as ‘difficult times’. It was ten years after Prime Minister Howard Moffat introduced the Land Apportionment Act of 1930. The law codified segregation in land ownership, and resulted in land dispossession of indigenous people who were forced into lower quality ‘Tribal Trust Lands’. The dual land tenure system became a thorny issue that stocked tensions which had been simmering from the First Chimurenga (1896-1897), and would fuel Black resentment leading to the outbreak of the Second Chimurenga / Liberation war (1964-1980).

Other discriminatory legislation affecting indigenous people at that time include:

Industrial Conciliation Act, 1934.

Excluded Africans from joining trade unions.

Public Service Act, 1921.

Bared indigenous people from employment in the civil service.

Immorality and Indecency Suppression Act, 1903.

Criminalized sexual acts between African men and White women.

Sale of Liquor to Natives and Indians Regulation, 1898.

Prohibited the sale of liquor to indigenous people.

The above exclusions and exploitation are not obvious in the paintings. The seemingly apolitical titles of the work may be compared to ‘The Grass Is Singing,’’ the title for a novel by Doris Lessing that deals with racial injustice. A White Zimbabwean, the Nobel Prize-winning author lived in Rhodesia between 1924 and 1949. Her novel, which was published in 1950 in the United States, is set in Rhodesia in the late forties. It was banned in the country and the writer was barred from returning, until independence in 1980.

The story of Ned Paterson and his outstanding art students is a classical narrative of underdogs inspired to attain unexpected triumph. Under different circumstances the success could be seen in the light of the White Savior complex and as part of the unredeemable civilizing mission. Paterson however is exonerated because he encouraged his students to value their own humanity, respect their own background, and retain their dignity. In the glowing terms of one of his students Job Kekana ‘‘He feared no one, yet respected all.’’

The extent to which Paterson influenced his students’ spontaneous artistic expression is evident in their pastoral paintings in which indigenous people represent biblical characters. Livingstone Sangos’ ‘The Good Shepherd’’ (1945) depicts Jesus as a Black man with dark wooly hair and eyes like ripe black berries. Sangos’ Messiah is very different from the longhaired blond man with blue eyes used by Europeans to subdue African slaves. Paterson himself also painted a figure of Christ dressed as an African Priest, on the wall of the sanctuary behind the altar in the Cyrene Mission Chapel which bears the world-famous distinct Cyrene style murals by his students.

Paterson describes the collection as ‘’not African art, but art from and by Africans.’’ His opinion could have been partially inspired by intimate knowledge of the artists and where their living conditions. The students who overwhelmingly have proselytized English and biblical first names did not insert overt political statements in their paintings, but considering their background informs deeper appreciation of their work.

The Stars Are Bright - Stanley Musa Nyahwa Photo Debbie Sears (The Curtain Foundation. From the exhibition The Stars Are Bright.

Nature is not seen from a materialistic and dualist perspective in the work that lends the exhibition its title. ‘’The Stars are Bright’’ by Stanley Musa Nyahwa depicts a magical bright tree in the foreground to a homestead under a starry night and full moon. The flowers of the tree mirror the stars, establishing a connection between the heavens (Mhepo) and the earth (Pasi). The huts in the background are connected to the tree by the pathways that mirror the branches of the tree intersecting with the trunk, which is rooted in the earth. The picture can be seen as a symbolic reflection of Shona cosmology.

Another magically colorful picture is ‘How Beautiful is Night’’ (1945) by Barnabas Chiponza. The painting is dominated in the foreground by colorful boulders in vibrant hues, intertwined with three trees with equally saturated colors. Traditionally the night is associated with witchcraft and death, unless the subject is hunting or warfare. The artists’ defiant optimism insists on seeing vibrant colors in spite of it being night time! The title of the work and its execution show Chiponza presenting his subject in the manner of a riddle.

A regular motif in the work on exhibition is the significance of home as represented by a homestead embedded in the landscape. Traditionally, home/ ekhaya / kumusha represents background, origin and the place where ones’ identity is rooted. In customary greetings it is common to ask how things are ekhaya / kumusha even when the person has been away from home for a long time. In the paintings the homestead is often depicted as a few crowded huts in a constricted space. Surrounded by the common rock formations, the huts appear both protected and hemmed in. Where the huts are tucked among the rocks, there is little or no space to raise crops or livestock. It is the antithesis to the large commercial farms, and ranches owned by White settlers, including land on which Cyrene Anglican Mission School is built, which was donated to the Anglican Church by a family called Banks.

Many of the landscapes painted by the students are populated with smooth boulders that have been attributed to inspiration from Matobo Hills. Uniformity and recurrence of the landmark becomes monotonous when seen in that reductive aspect alone. The UNESCO World Heritage Site, lying 25 kilometers from Cyrene Mission, is revered for its sacred caves and religious shrines. It was also the last stronghold for Ndebele warriors, and the site of fierce battles with White settlers in the Second Ndebele war that was part of the First Chimurenga. Literally in this place indigenous people found themselves between a rock and a hard place.

William Nyati, Rocks and Flowers (1945). Photo Debbie Sears © The Curtain Foundaton. From the exhibition The Stars Are Bright

Willie Nyati distills the terrain to its barest terms with his succinctly titled ‘Rocks and Flowers’. Nyatis’ celebration of the landscape has no sign of human habitation. The title sounds great for a European style still life painting, but in a local context it feels poignant, understated, and subversive. The abstract rendering of profuse rock outcrops and vegetation is framed with decorative patterns that are also used on traditional implements.

Another picture illustrating the relationship with the land is Crispin Chawiras’ untitled work dated 1945. The painting shows a man carrying an axe, another digging with a hoe, and a third sitting by a fire with a bucket and smaller object on the other side of the hearth. This picture of communal farmers toiling in the land, reads like a proverb about persons expending themselves against minimal resources that could never yield significant results.

The social scene comes to life in Basil Majahana Mazibukos’ painting with the deadpan title ‘Story of my life,’ (1947). The piece shows a vibrant community with different social classes, engaged in various activities, in a place where tradition and modernity seem to coexist. Mazibukos’ sunny outlook on life is on display again in another artwork created the same year titled ‘The careless village.’ The second piece depicts a carefree, merrymaking community at work and play whose jollification seems wildly decontextualized. On a different note his piece titled ‘Life in Bulawayo Location’ depicts an unpopulated scene with a cluster of huts nestled among the rocks. Ironically the deserted homestead shows no sign of life. It is the kind of austere environment described in indigenous parlance as a ‘no dog or chicken’ situation. The image prompts a nagging question, “Where have all the people gone?’’

‘Life in Bulawayo Location’ - Basil Majahana Mazibuko (1947). Photo Nyamzombe Nyampenza © The Curtain Foundaton. From the exhibition The Stars Are Bright

Popular with a foreign audience in their time, the pictures carry a different weight for local indigenous audiences today. It would not be realistic to expect an similar reaction from generations whose forebears were exploited and condemned to servitude. For Africans the value of the pictures extends beyond style and aesthetics. The formerly rejected, neglected, and abandoned artworks are uniquely placed to tell compelling stories that were not obvious to a privileged minority. As Bob Marley, borrowing from the bible famously sang, ‘’The stone that the builder refuse, will always be the head cornerstone.’’

The Stars Are Bright exhibition is showing at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Harare until 31 October 2022.

All copyrights observed

Comments